It took me a while to comprehend how objects worked in Ruby. If I had to explain it to my younger self again, here’s how I would do it.

An object in object-oriented programming could be anything but let’s ground ourselves with something simple.

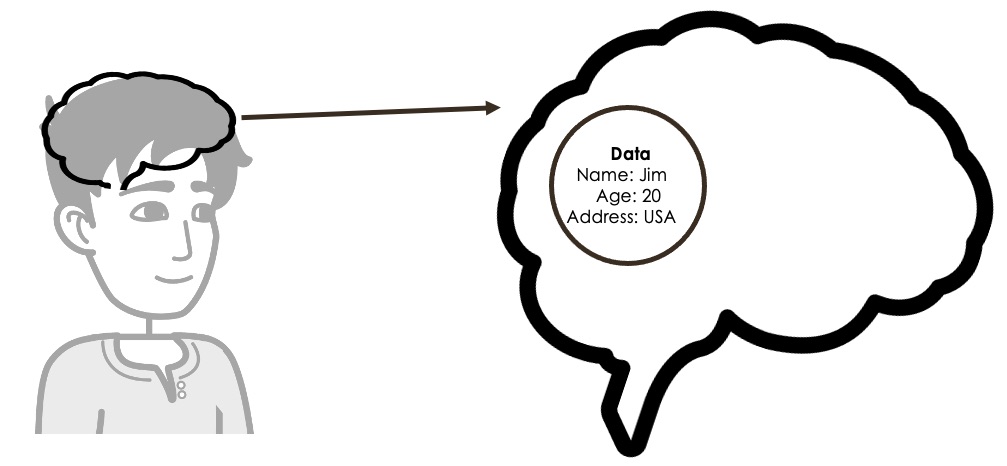

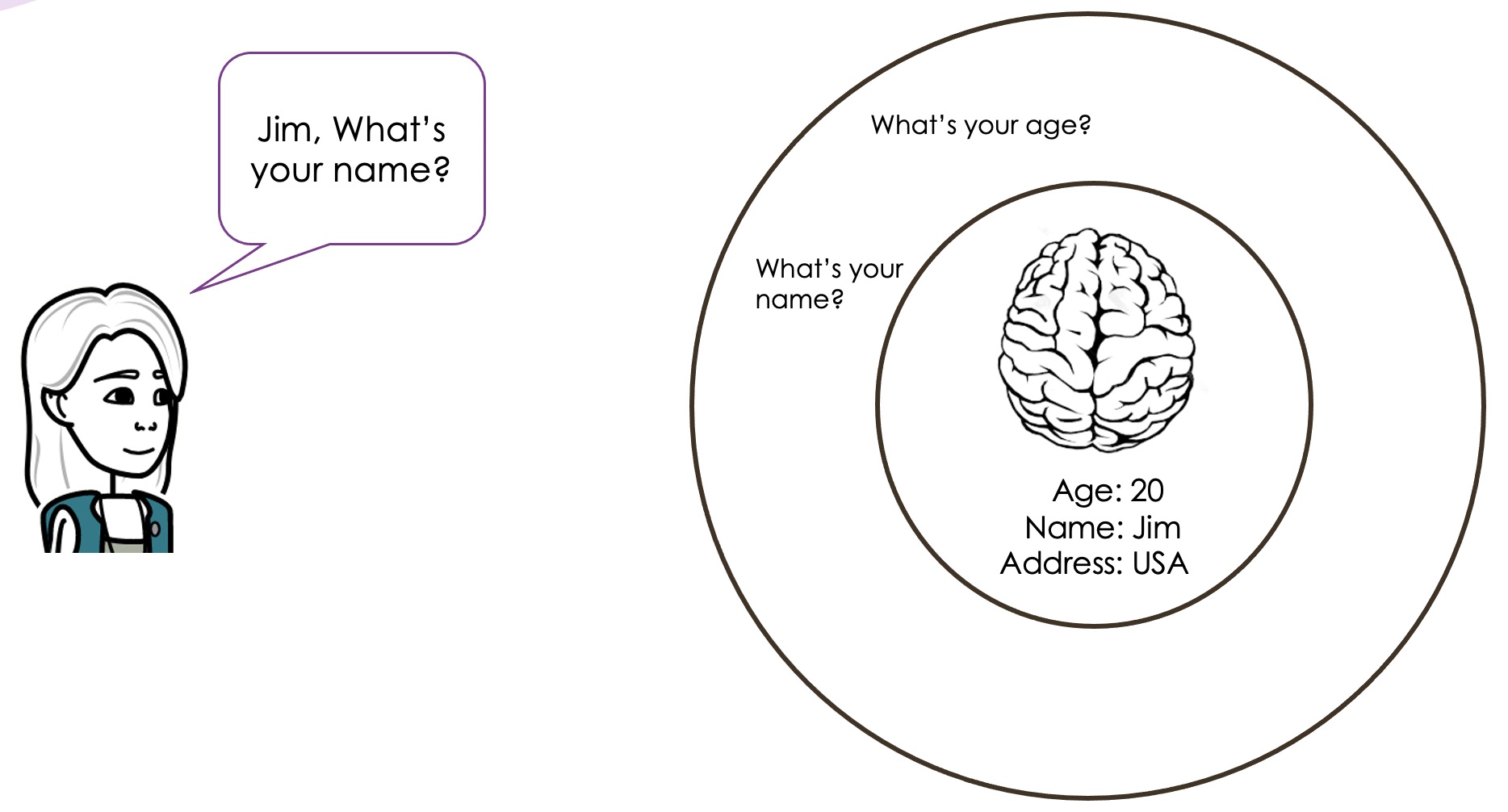

Let’s use Jim — a person — as the object.

Like any other human, Jim stores information in his brain.

I’m going to grossly over-simplify the brain into two parts. We’re not learning biology here. Objects can store data and they have behaviors. This simplified model shows how objects store data and behave by communicating with other objects.

I won’t know the data inside Jim’s brain unless he chooses to share it with me. Jim’s data is private to him.

This is similar to when a cop apprehends a suspect and tells him “you have the right to remain silent”. The cop doesn’t know what the suspect knows.

All data inside the circle is isolated, or in programming jargon — it is ENCAPSULATED. It is isolated from all things outside the circle.

I can’t telepathically read Jim’s mind.

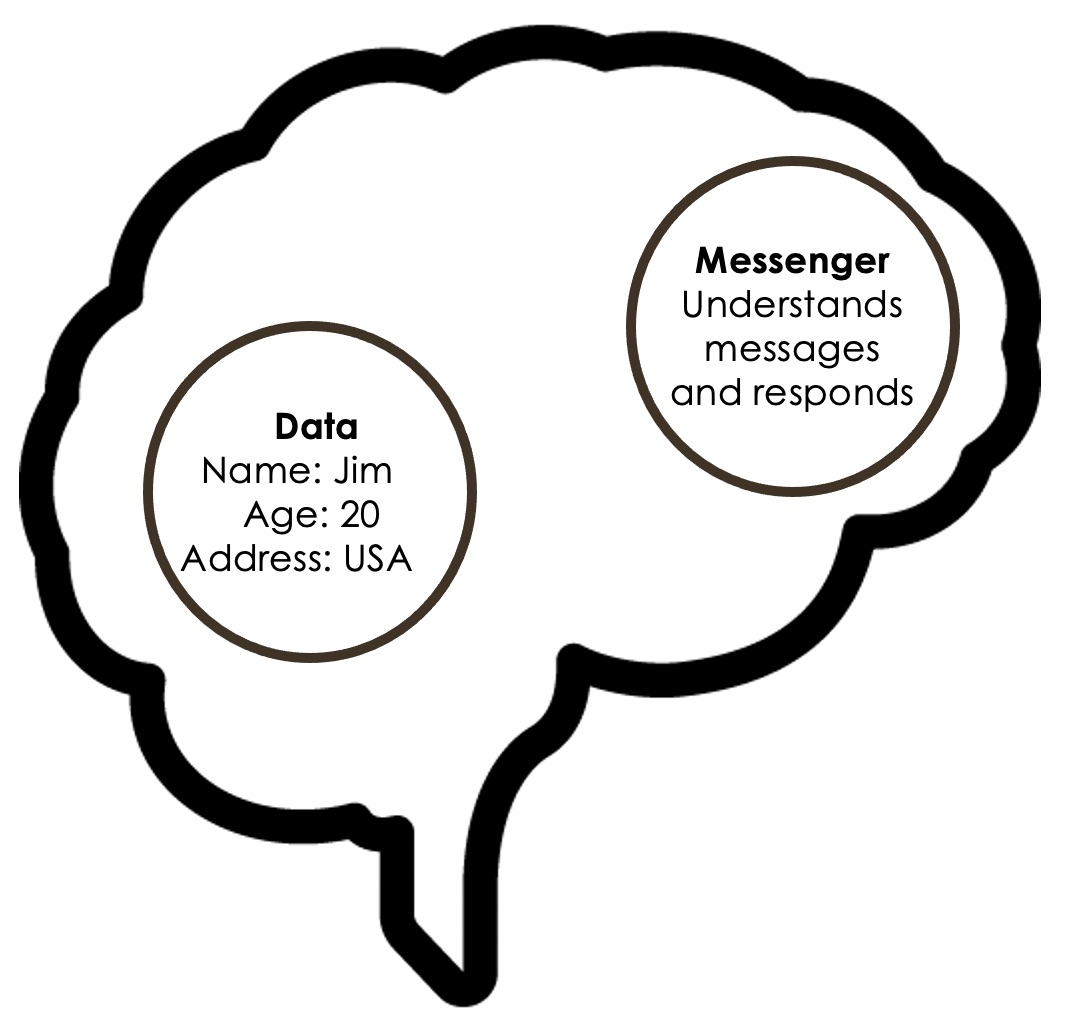

If I ask “What’s your name?” — his brain needs to understand my request (message) and have a way to respond to it.

The second circle in the over-simplified brain in the messenger. It responds to those questions it can understand. Unlike us, the messenger has direct access to Jim’s data circle.

Using this analogy we’ll understand how objects store data and how they understand messages and respond to them.

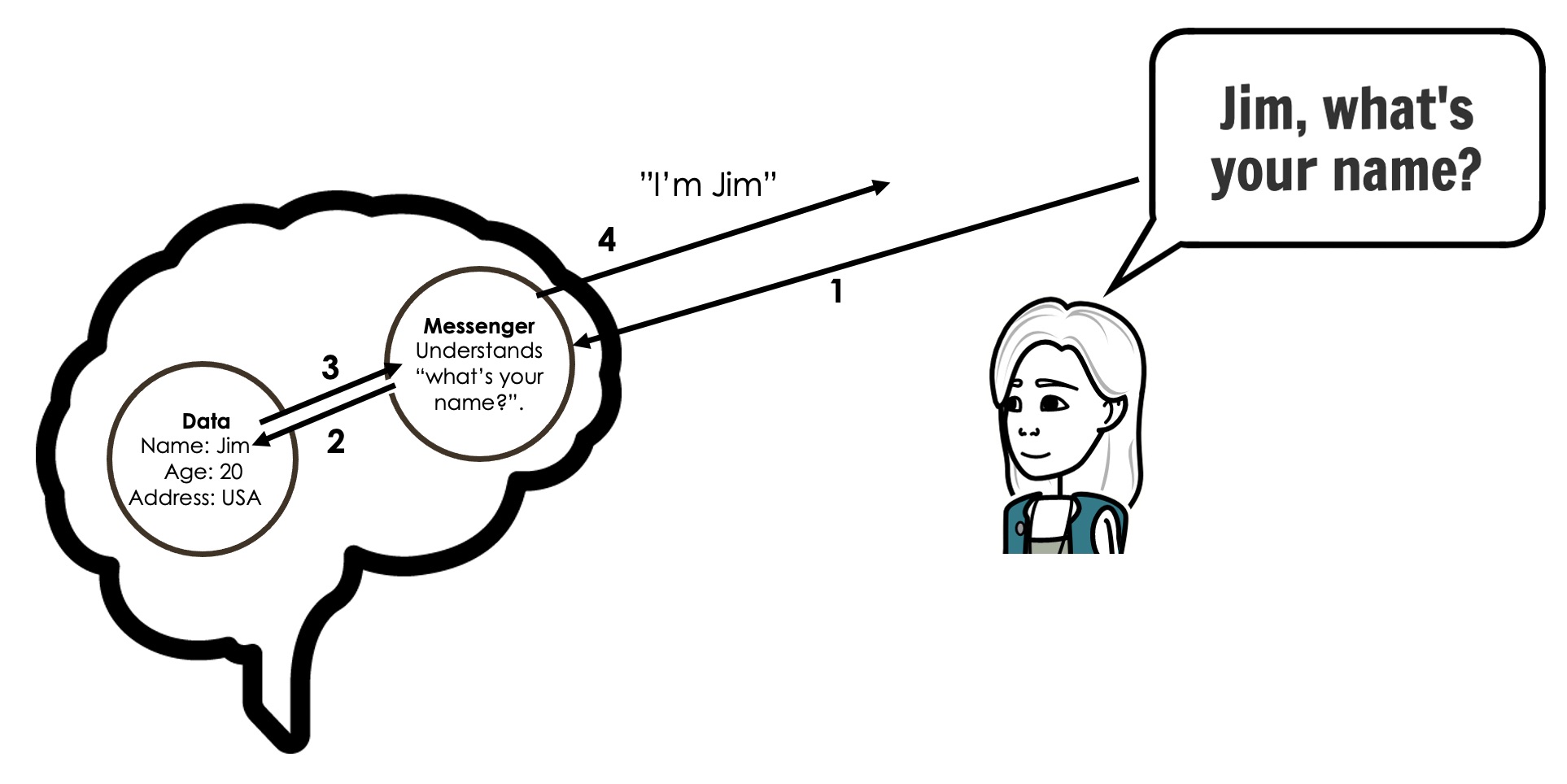

Asking a question

Here’s what happens when you ask Jim his name:

- Jim receives a question

- If the messenger circle understands the question, it can ask the data circle for Jim’s name.

- Data circle sends Jim’s name to the messenger.

- The messenger responds with ‘Jim’.

The messenger is the middle man between you and Jim’s data. You can’t get to Jim’s data directly without first going through the messenger circle.

Let’s redraw the data and the messenger circles as two concentric circles. The inner circle is the data circle and the outer circle is the messenger.

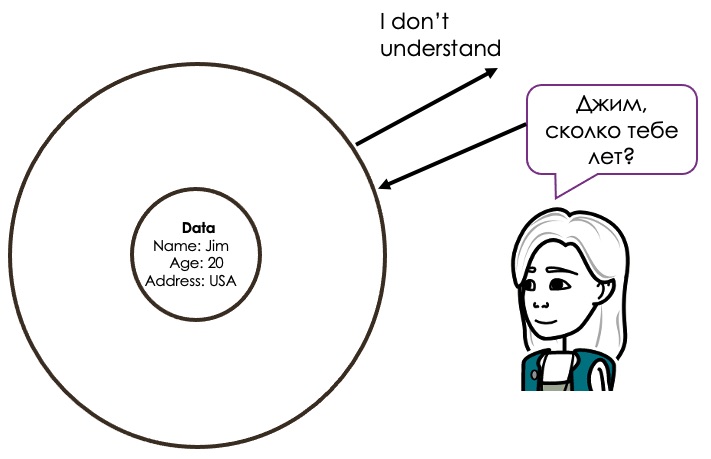

What happens if you ask a question that Jim’s messenger can’t understand? You ask his name in Russian but he doesn’t speak Russian.

Even though Jim’s age is available in his data circle, the messenger circle doesn’t understand сколько тебе лет. The object doesn’t respond with Jim’s age.

Using the above analogy, we covered that an object’s data is encapsulated within the object (stays private) unless it is exposed by the messenger.

Let’s apply our analogy to Ruby code.

Jim as a Ruby Object

In Object Oriented programming, we create objects — known as instantiating — from a class. A class is like a factory template.

Jim is a person. We’ll ask the Person factory (class) to build a person object Jim. In other words, we’ll instantiate Jim from the Person Class.

Let’s create an empty Person class.

class Person

end

The Person class allows us to pass two pieces of data (name and age) to objects we create from it. The Person’s name and age. We use a special Ruby initialize method to pass that data as two parameters.

class Person

def initialize(name, age)

end

end

Let’s instantiate a Jim object from the Person class and reference it in a jim variable. If you inspect it, you’ll notice it isn’t holding any data.

jim = Person.new("Jim", 20)

jim.inspect # => <Person:0x00007fed7ac3a2c0>

That’s because we forgot to store the parameters we passed into the Person class as instance variables. Let’s do with a @name and @age instance variables.

class Person

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

end

jim = Person.new("Jim", 20)

jim.inspect # => "#<Person:0x00007fb8428be7a8 @name=\"Jim\", @age=20>"

The object is now storing a name and age. Instance variables are the data circle we talked about in our analogy. Remember, we don’t have direct access to that data. Let’s try accessing Jim’s name and see what happens.

jim.@name # => Syntax Error. You cannot call on instance variables directly from an object.

jim.name # => undefined method `name'

His name and age are stored in instance variables as private data. We need a messenger to understand our request for Jim’s name and respond with his name. In object oriented languages like Ruby, this messenger is called a method. In this case, it’s a getter method because it’s getting a piece encapsulated data from Jim and exposing it outside the object..

class Person

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

# Add a getter method to get Jim's name

def name

@name

end

end

jim.name # => "Jim"

It worked! We write a getter method, which is a messenger between us and Jim’s data. By writing jim.name, we send a message name to Jim. The name method recognizes that message and returns the value of @name.

The name of the method could be whatever you want it to be. You could write:

def what_are_you_called

@name

end

jim.what_are_you_called # => "Jim"

You could also return anything from a method including:

def name

"My name is " + @name

end

jim.name # => "My name is Jim"

Or you could say something sassy:

def name

"I won't tell you!"

end

jim.name # => "I won't tell you!"

The object has total control in how it chooses to respond to outside requests.

We can ask for Jim’s name but we still can’t ask for his age. Let’s write a getter method that will respond to jim.age.

class Person

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

# Getter method to get Jim's name

def name

@name

end

# Getter method to get Jim's age

def age

@age

end

end

jim.name # => "Jim"

jim.age # => 20

Let’s write a method that asks Jim to tell us his name and age in one sentence.

def name_and_age

"My name is " + @name + " and my age is" + @age

end

jim.name_and_age # => "My name is Jim and my age is 20"

Setter Methods

What if we wanted to modify Jim’s age?

jim.age = 30 # => NoMethodError: undefined method `age='

We get an error. Look at the error message. Jim doesn’t understand the method (message) age=. That method doesn’t exist in the Person class.

We can fix this by writing a setter method. Why a setter? Because it sets a new value.

class Person

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

# setter method to SET Jim's age.

def age=(num)

@age = num

end

end

jim.age = 30 # No errors

You’re probably wondering why the method was named age=() but we called jim.age = 30. This is Ruby syntactic sugar.

# When you set a variable like below:

jim.age = 30

# Ruby actually runs this. Try it in your console!

jim.age=(30)

# It's just prettier to write jim.age = 30.

Pop Quiz Hotshot — If you ask for Jim’s age jim.age you’ll get an error. Why?

It’s because we erased the getter method that gave us Jim’s age. Let’s put it back. I wanted to show that setter methods can work independently of getter methods.

class Person

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

# setter method to SET Jim's age.

def age=(num)

@age = num

end

# Getter method to get Jim's name

def name

@name

end

end

jim.age = 30

jim.age # => 30

attr_reader, attr_writer, attr_accessor

Ruby was made for developer happiness. In Ruby you’ll rarely see getter and setter methods explicitly written as above.

There’s a shortcut to having Ruby write them for you.

attr_readerwrites a getter method.attr_writerwrites a setter method.attr_accessorwrites a getter AND setter method.

Let’s open the Person class again and have attr_reader create a getter method for name.

class Person

attr_reader :name

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

end

jim.name # => "Jim"

Notice we used :name. That’s a symbol. The symbol needs to be named the same as the instance variable that is holding the data.

For example in name is referenced by @name instance variables, then the attr_ symbol should be named :name.

# This won't work because the instance variable is not @name.

# Modify it to attr_reader :what_am_i_called to make it work.

attr_reader :name

def initialize(name, age)

@what_am_i_called = name

end

You can add multiple getters on one line separated by commas.

attr_reader :name, :age

Let’s allow other objects to ask Jim for his name and age but only allow other objects to set Jim’s age.

attr_reader :name, :age

attr_writer :age

Let’s say Jim is a very open person, we can add getters and setters to his name and age like this:

attr_accessor :name, :age

Other objects can now get and set jim’s name and age.

There’s nothing magical about these attr_ methods. Ruby writes the same exact getter and setter methods we wrote manually above.

attr_reader :name # This

# is the same as writing:

def name

@name

end

attr_writer :age # This

# is the same as writing:

def age=(num)

@age = num

end

attr_accessor :age # This

# Writes both the getter and setter methods for age.

def age

@age

end

def age=(num)

@age = num

end

Instantiating Objects from Classes

Since the Person class is a factory, we can create (instantiate) other people with different names and ages.

class Person

# Add getter and setter methods to both name and age.

attr_writer :name, :age

def initialize(name, age)

@name = name

@age = age

end

end

# Create 3 different Person objects.

jim = Person.new("Jim", 20)

sally = Person.new("Sally", 40)

bob = Person.new("Bob", 70)

jim.name # => "Jim"

sally.age # => 40

# Let's change Sally's age

sally.age = 100

jim.age # => 20

sally.age # => 100

bob.age # => 70

jim.age + sally.age + bob.age # => 190

Notice how each object tracks it’s own internal data. As we’ve mentioned before, in object oriented languages, objects have data (instance variables) and behavior (methods).

Example with Cash Registers

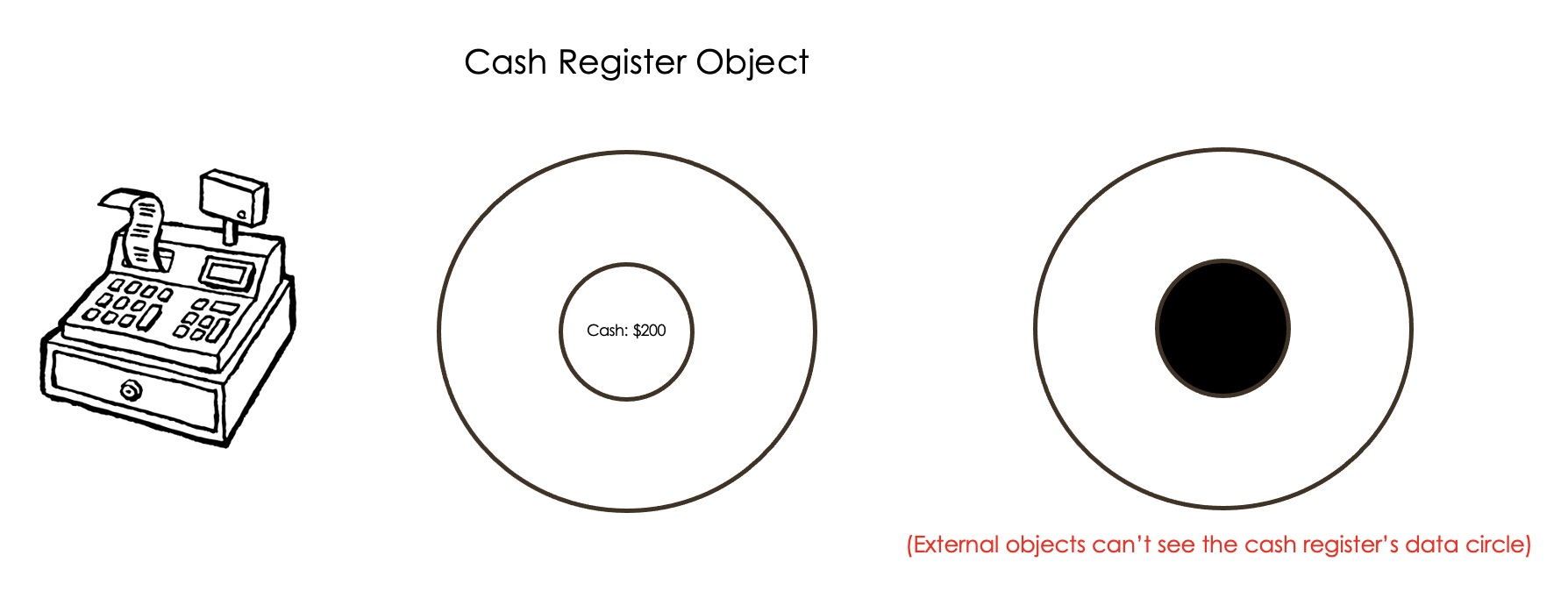

Let’s apply our knowledge of objects to a cash register.

class CashRegister

def initialize(cash)

@cash = cash

end

end

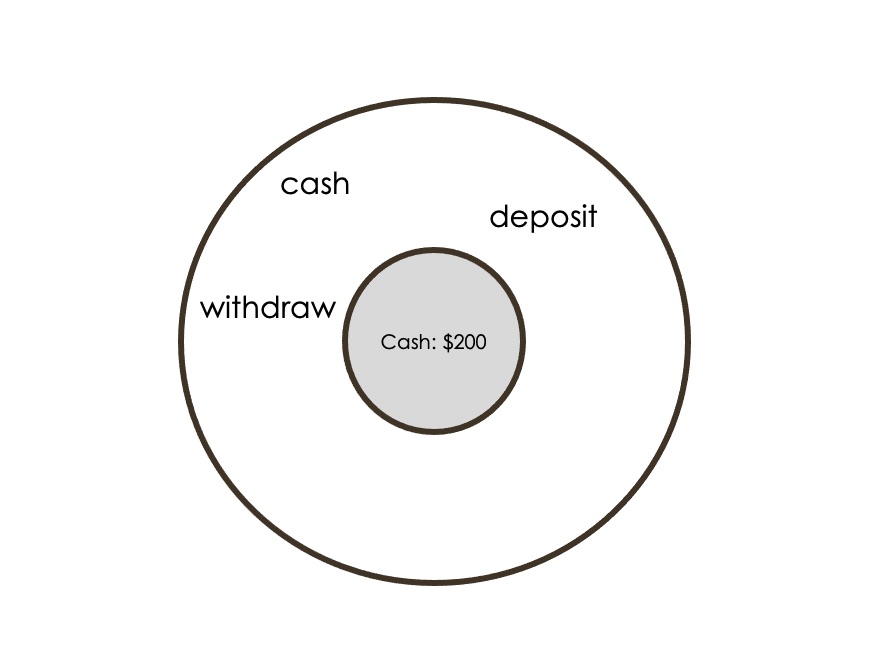

cash_register = CashRegister.new(200)

The cash register currently holds the cash total as data (inner circle).

To external objects, that cash total is not known. That data is encapsulated to the cash_register object.

If we send a message cash_register.cash it won’t respond with the total.

cash_register.cash # => NoMethodError: undefined method `cash'

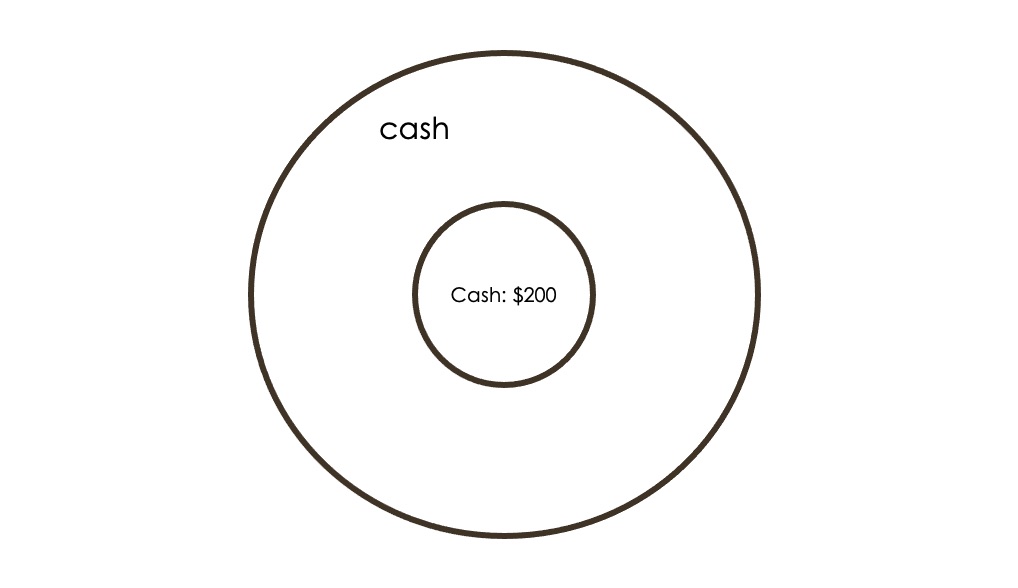

Let’s create a getter method cash using attr_reader :cash to get the @cash value.

class CashRegister

attr_reader :cash

def initialize(cash)

@cash = cash

end

end

cash_register = CashRegister.new(200)

cash_register.cash # => 200

Methods are behaviors

How do you know which messages (methods) an object should understand? Ask yourself, what should your object be able to do?

A cash register should be able to store cash (data) and you should be able to check the value of it, deposit money, and withdraw money from the register.

As a person trying to use this object, all you see is this object understanding three messages withdraw, cash_sum?, and deposit.

As an outsider passing a message to the cash register, you don’t need to worry about HOW it handles what you tell it to do. The cash register will do that internally. Again, that’s the idea of encapsulation. You trust the object to handle the messages you send to it without you meddling in them.

Let’s add withdraw and deposit methods to the CashRegister class.

class CashRegister

attr_reader :cash

def initialize(cash)

@cash = cash

end

# Added method to deposit cash.

def deposit(amount)

@cash = @cash + amount

end

# Added method to withdraw cash.

def withdraw(amount)

@cash = @cash - amount

end

end

cash_register = CashRegister.new(200)

cash_register.cash # => 200

cash_register.deposit(500)

cash_register.cash # => 700

cash_register.withdraw(100)

cash_register.cash # => 600

Sending Messages

To send a message to an object, you first specify the object followed by a dot and then the message.

cash_register.cash # => 200

Let’s say you want to deposit or withdraw money into / from the cash register. The next question is how much? You can pass the amount as an argument with the message like this.

cash_register.deposit(25)

cash_register.withdraw(50)

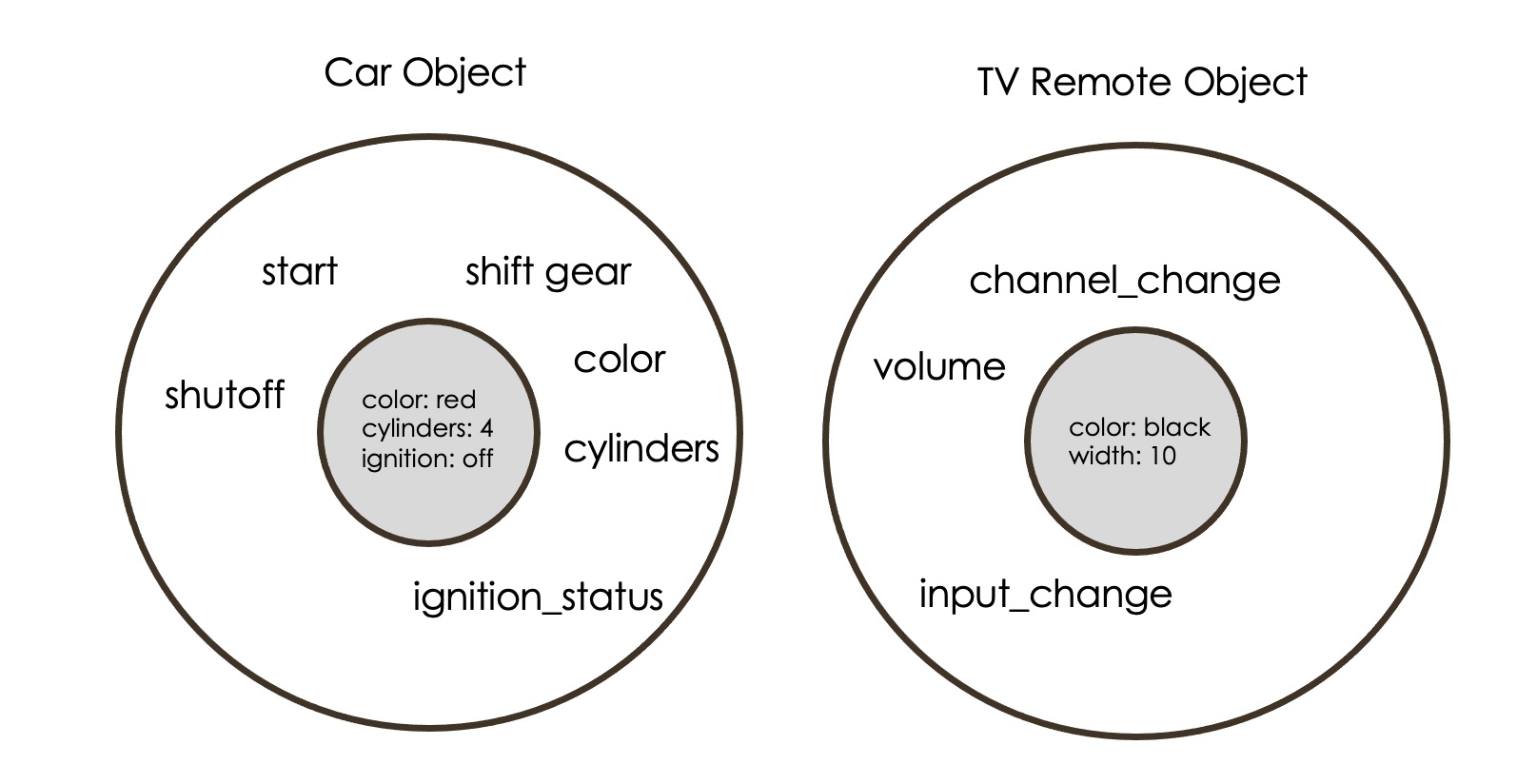

More examples of objects

Let’s take a look at how other objects might look like.

Notice that with the TV remote object, I cannot send a color or width message. Those aren’t defined in the outer circle. They haven’t been written as methods yet.

The remote will respond to remote.color but it will be with an error message. Objects ALWAYS respond to messages. The response might be an error message and not the value you were expecting.